Phishing Simulations: Legit Training or BS?

Exploring the Controversy: How Effective Are Phishing Simulations and Security Awareness Training in Reality?

Last week, Matt Linton wrote On Fire Drills and Phishing Tests on the Google Security Blog, which caused quite a stir. He boldly claimed that “There is no evidence that the tests result in fewer incidences of successful phishing campaigns,” and even points to one study that showed that phishing simulations had an adverse effect. This post is far from the first time someone has made this claim. In his blog post, Security Awareness Training, famed security technologist Bruce Schneier made similar claims in 2013. He even went as far as to say, “The whole concept of security awareness training demonstrates how the computer industry has failed.” These posts got me wondering if there was any truth to these claims. Luckily, phishing test accuracy is easily measurable, and there’s a wealth of research papers and data on this topic. Let’s dive in.

The Evidence

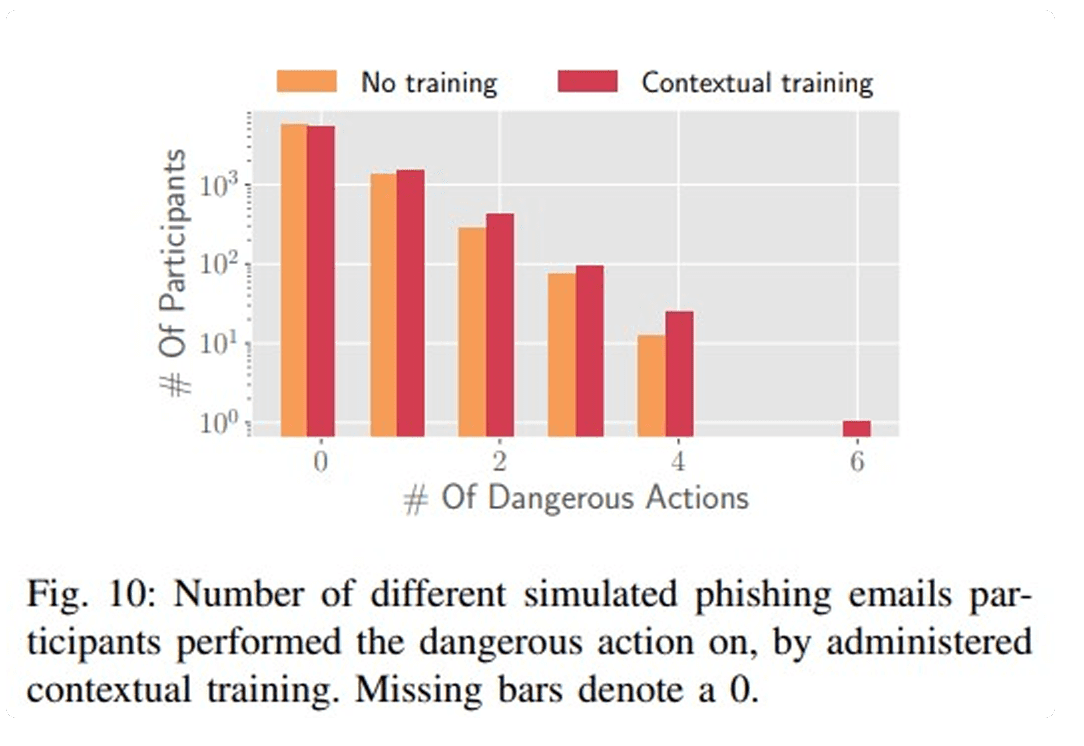

Matt Linton’s blog post references a study called "Phishing in Organizations: Findings from a Large-Scale and Long-Term Study" from researchers at ETH Zurich. It involved 14,773 employees in a private organization in Switzerland and compared the effectiveness of embedded warning notifications against training pages. The results showed that embedded warnings effectively reduced click-through rates and improved the reporting of phishing emails. However, the same study found that training pages, when combined with simulated phishing exercises, did not improve—and in some cases even increased—employees' susceptibility to phishing attacks. The stats were as follows:

- Click Rate - 3,087(control) vs. 3,593(embedded training)

- Dangerous actions - 2,155(control) vs. 2,730 (embedded training)

A Comparative Analysis

While this study may at first seem pretty damning, it’s essential to look at similar studies and the design of the experiment. I found the following papers that contradicted the findings above.

A large-scale anti-phishing training involving over 31,000 participants and 144 different simulated phishing attacks revealed that 66% of users did not fall victim to credential-based phishing attacks even after twelve weeks of simulations. The study showed significant improvements in users' ability to recognize phishing attempts over time, particularly when training was frequent and tailored to individual risk levels.

"Don’t click: towards an effective anti-phishing training. A Comparative Literature Review"

This review by Daniel Jampen and colleagues at Zurich University of Applied Sciences categorized and analyzed multiple studies on anti-phishing training programs. The review searched the literature deeply, evaluating various methodologies and outcomes associated with anti-phishing training across several academic and professional studies. They found that training generally had a positive result. For instance, the study by Doge et al. highlighted that embedded training, where training exercises are integrated into everyday work activities, significantly improved user behavior over time. In this study, only 24.5% of participants who received such training failed the test, compared to 47.5% in the control group who received no training. These statistics contradict the findings from the ETH Zurich paper that embedded training increases the likelihood of clicking on links.

Moreover, Gordon et al.’s retrospective study across six US healthcare institutions involving nearly 3 million phishing emails sent from 2011 to 2018 provided substantial statistical backing. It showed that repeated phishing campaigns significantly lowered the likelihood of employees clicking on phishing emails, with the odds of clicking reduced by almost 50% after more than ten campaigns. These findings demonstrate the potential of regular and repeated training to condition and improve employee responses to phishing attempts.

Vendors

I’ve intentionally omitted research from vendors selling products in this space as they are biased. That being said, most of these vendors publish stats on efficacy and provide dashboards for organizations to track click-through rates over time.

What might be wrong with the ETH Zurich Study?

There are a few reasons why the ETH Zurich study's click-through rates might be slightly increasing.

1. False sense of security:

Firstly, the training page may have created a false sense of security in its design. The authors call this out:

"One possible explanation that emerges from the questionnaire responses was a false sense of security that is related to the deployed training method: out of the respondents who remembered seeing the training page, 43% selected the option “seeing the training web page made me feel safe,” and 40% selected the option “the company is protecting me from bad emails.”

Perhaps unintentionally, the training reassured participants that the company's security measures were sufficient, making them less vigilant in real-world scenarios.

2. Voluntary Training & Lack of Engagement:

The ETH Zurich study used voluntary embedded training. Participants weren't obligated to complete the training after clicking a phishing link. This decision contrasts with many other studies showing positive results from mandatory training programs. For example, Doge et al. (as cited in paper 2) found that:

"Embedded training, where training exercises are integrated into everyday work activities, significantly improved user behavior over time. In this study, only 24.5% of participants who received such training failed the test, compared to 47.5% in the control group that received no training."

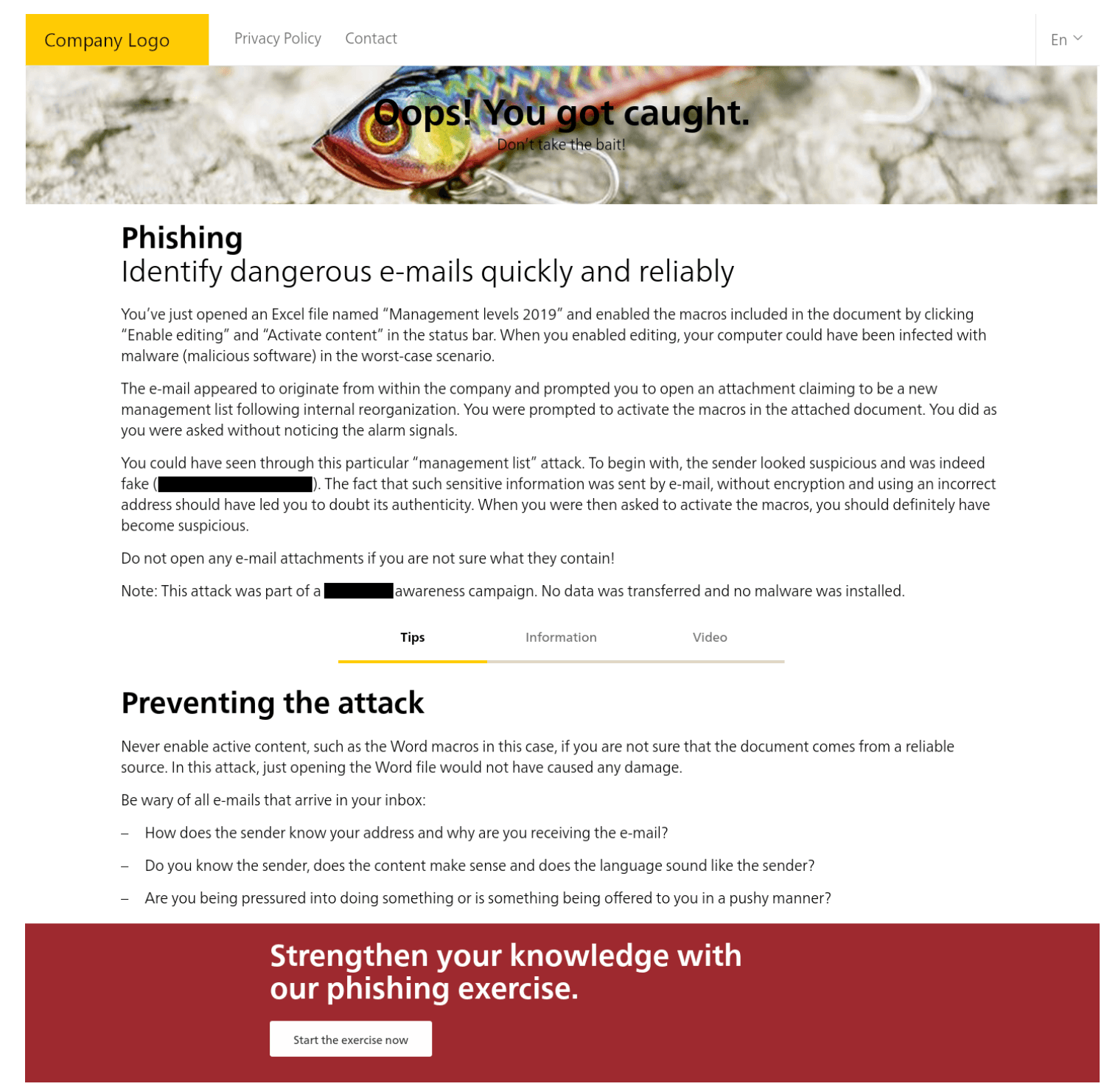

4. Limited Scope & Generalizability:

While the ETH Zurich study boasts a large sample size and a long duration, it's crucial to acknowledge its limitations. The study focuses on a single organization within a specific industry and location. The training content and delivery methods might differ from those of other organizations or sectors. Additionally, the study doesn't explore the effectiveness of the training content itself. Was the material engaging, relevant, and easily understandable? All we know about the training is that it was from an unspecified vendor and looks like the screenshot below.

Takeaways

I think it’s fair to say that Phishing Simulations and Security Awareness Training as a whole work. But for that to happen, you need to create effective training. It will probably be ineffective if you view it as a check-the-box exercise for compliance. Like any program, it needs love, attention, and effort to succeed.

There’s a massive opportunity to build better tools and programs here:

-

Personalized training

Stock training produces stock results. Tailoring training to an organization and specific individuals' behavior, role, and tool use is crucial. -

Realistic Spearphishing

Attacks are changing, but training templates stay the same. Attackers are increasingly using spearphishing and whaling techniques. Simulations need to be a lot more realistic than a fake PayPal page. -

Auto-adjusted difficulty

Standards, like the NIST Phishscale, outline factors that can be included to make phishing emails harder or more accessible. These can be used to increase difficulty as users become more vigilant. -

New modalities

Attackers use SMS, Social Media, Voice, and other modalities daily. Training must account for these attacks' increasingly multifaceted nature to be effective. -

Don’t make it punitive

It’s 2024, and clicking on a link in a browser is okay. What matters is what happens after you click the link. The next generation of tooling should focus on user behavior and building a positive security culture.